Introduction

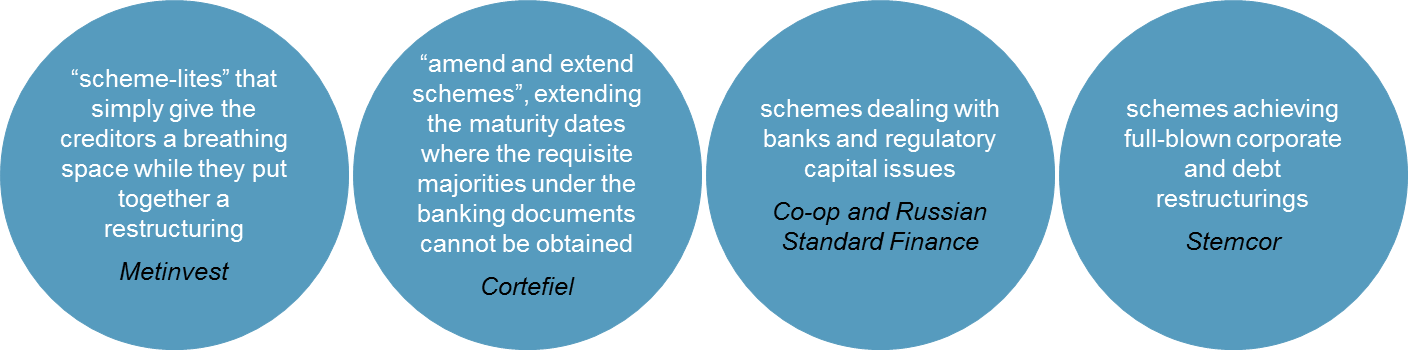

Is there anything that cannot be done via an English scheme of arrangement? In recent times we have seen proposed:

Indeed, in one week in November, A&O came before the court on three very different schemes referred to in this bulletin in the course of a single week. At the same time, the envelope is being pushed regarding the use of schemes for foreign companies (as discussed below).

Given that no creditor scheme has failed in recent memory where that scheme has been approved by the requisite statutory majorities, creditors and debtors could be forgiven for thinking that nothing is too much. Indeed, on 17 December, Mr Justice Newey sanctioned the Codere scheme (after 97% by value of the creditors agreed to submit themselves to the jurisdiction of the English court), notwithstanding the comments of the judge at the convening hearing that the introduction of a new English company was a kind of forum shopping. Newey J did not disagree but said that forum shopping can be good if aimed “to achieve the best possible outcome for creditors". However, as discussed in this bulletin, the English court has put out a clear message in recent cases that schemes are not commoditised products and the paperwork supporting them had better be in order. Furthermore, the English court may be prepared to push back on certain issues in order preserve the international standing of the English scheme of arrangement as a respected restructuring tool.

Jurisdiction

When can an English scheme be used in respect of a foreign company? The “sufficient connection” test applied by the English court in such cases has steadily loosened over the years:

- In La Seda involving a Spanish company, not only were the finance documents governed by English law with an exclusive jurisdiction clause in favour of the English courts but the majority of the lenders were based in the UK

- In Primacom involving a German company, the finance documents were English law governed but there were no UK lenders

- In Magyar Telekom involving a Dutch company, the finance documents were New York law governed but the centre of main interests of the company was shifted to the UK

- In Apcoa involving a German company, the governing law of the finance documents was amended from German to English law

- In Codere involving a Luxembourg company, a new UK based company was established to take over the liabilities originally issued by the Luxembourg company.

Although the courts have expressed reservations around this sort of jurisdictional manoeuvring, none of the cases referred to above actually failed on jurisdiction grounds. On the other hand, neither was there any serious challenge. It is still possible therefore that a court in 2016 could hold that a scheme goes too far when trying to apply the “sufficient connection” test.

Impact of European legislation

The interplay between the European Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings1 (which governs the jurisdiction for and recognition of certain insolvency proceedings in Europe) and the European Judgments Regulation2 (which governs the recognition and enforceability of judgments) has still not been fully resolved. There is an argument that European legislators did not intend there to be any gap between these two regulations such that the English scheme must fall within the scope of one of them. Quite clearly and deliberately, schemes are not included in the list of UK insolvency proceedings contained in the annexes to the European Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings (or the recast of this Regulation that will come into force in 2017). Had they been included, it would not have been possible to use an English scheme where the company did not have a UK centre of main interests or establishment. However, on the face of it, schemes fit awkwardly into the wording of the Judgments Regulation. The practical effect of this debate is that jurisdiction must now be demonstrated in respect of the scheme creditors and not just the debtor proposing the scheme. English governing law alone is no longer enough. The Judgments Regulation requires that, in the absence of all creditors submitting to the jurisdiction of the English courts (for example, in the jurisdiction clause in a loan agreement), it is necessary to establish that at least one creditor is domiciled in England3 and that it is expedient to deal with all the creditors under the same proceeding. This can be challenging in the context of a noteholder scheme where the domicile of underlying noteholders can be difficult to ascertain.

Despite an increased focus on the issue in recent cases such as Van Gansewinkel Groep BV, no decision has been made on whether the Judgments Regulation applies to schemes; the English court has proceeded on the basis of arguments that it has jurisdiction whether or not the Judgments Regulation applies. Therefore, those proposing a scheme must present appropriate evidence to satisfy the court that it does have jurisdiction under the Judgments Regulation or be the first to successfully argue that the Judgments Regulation does not apply.

Class composition

Under an English scheme, creditors must be divided into classes, depending on their rights and interests. One class schemes are often desirable as they reduce the prospect of minority blocking stakes. However, it is often the case that different creditors are treated slightly differently (albeit for good commercial reasons) and so the question arises as to when those differences are sufficient to result in separate classes.

In recent cases, the courts have cautioned against the trend of relying on single class schemes, either by playing down any differences between the creditors or by structuring the scheme so that, theoretically, the rights are available to all creditors even if, in reality, they are not. We expect further judicial scrutiny on the class issue in 2016 and so those proposing schemes should be prepared to be challenged on class composition at the convening hearing.

Relevant comparator analysis

The courts have also made clear that they expect the quality of information made available to creditors, and the evidence presented to the court, to be of a sufficient standard so as to allow creditors and the court to come to an informed decision as to whether they oppose the scheme or support it. The evidence presented to the court must be appropriate to allow it to critically assess the application, particularly in the absence of creditor opposition. Recent cases have included criticism of the manner in which certain information has been presented by debtors to their scheme creditors. In particular, where the scheme is proposed as an alternative to insolvency proceedings, we anticipate that the courts will expect more rigour to be brought to the comparator analysis in scheme cases in 2016.

Lock-up agreements and consent fees

Consent fees and lock-up agreements have been used in scheme cases for years and play an important part in giving the debtor and creditors some visibility as to whether the scheme will be successful. As long as such arrangements are structured carefully, the court has not considered them to create class issues or raise concerns as to fairness. However, in a number of cases in 2015, the court has indicated it may be time to re-examine certain matters that have become market-standard.

European alternatives to English scheme

While the English scheme remains the restructuring procedure of choice, the rest of Europe has not been standing still in this area. Credible alternatives are being developed in a number of jurisdictions including Spain, the Netherlands and Germany. A&O’s strong European network is well placed to assist debtors and creditors in deciding upon the best procedure to be used in any particular case.

A snapshot of our recent experience

We have been involved in a number of high profile schemes of arrangement in recent years (“If they don't agree, we’ll just scheme them” February 2013 and Vinashin – An English solution for an Asian problem 28 October 2013). The three case studies set out below (which all came before the English court in November of this year) demonstrate the versatility of the English scheme of arrangement and how wide its potential application can be.

Stemcor Trade Finance Limited

The scheme of arrangement of Stemcor Finance Limited was an integral part of the second restructuring of the Stemcor group. A&O (banking, corporate, anti-trust, tax and regulatory expertise from 14 A&O offices worldwide) acted for the co-ordinating committee of lenders on the first restructuring in March 2014 and the co-ordinating committee of senior lenders on the second restructuring which completed in October 2015. In working on both restructurings of the Stemcor group we have developed expertise in dealing with issues facing the commodities sector. In particular, given the bilateral uncommitted nature of trade finance facilities, borrowers in this market are particularly susceptible to liquidity issues and potential insolvency and A&O understands the vital importance of securing trade finance facilities for borrowers in distress in this sector.

The second restructuring involved a demerger of the Stemcor Group into separate core and non-core businesses. All lenders retained a limited recourse debt claim against the non-core business and a reduced debt claim against the core business, while those lenders that supported the core-business (by providing new syndicated trade finance and borrowing base facilities) also received equity in the core business. The restructuring was complex involving a pre-planned administration, scheme of arrangement and release of junior debt and was implemented successfully following challenges from a junior lender and certain shareholders.

The two restructurings involved expertise in trade finance (and the negotiation of syndicated trade finance facilities), a knowledge of the distressed market (given that the underlying economic interest in the company’s debt was held by a number of different parties including distressed investors) and the ability to react quickly in a crisis (for example A&O had to take instructions from over 40 lenders in a very limited period of time when the shareholders took certain hostile action to put the company into liquidation). In the specific context of schemes of arrangement, a number of issues were raised including the class issue discussed below.

Scheme single class questioned (but not judicially resolved)

The scheme convening hearing was heard by Mr Justice Snowden, one of the judges who is currently considering what limits should be placed on the English court’s jurisdiction in relation to schemes. Under the scheme, senior lenders who participated in the trade finance facilities received equity in the core business pro rata to their participation. The “anchor shareholder” (being the lender holding just under 20% of the debt before the launch of the scheme and entitled to hold at least 15% of the equity under the scheme) was also given additional rights to control a majority of the board and appoint executive management. Furthermore, the anchor shareholder was entitled to receive an additional 3% of equity provided it achieved a specific value threshold for the business on exit. These features led Snowden J to question whether the anchor shareholder was really able to vote in the same class as other senior lenders – demonstrating that, even in circumstances where there is strong creditor support for the restructuring, the court will not simply rubber stamp proceedings. As there was already sufficient support for the scheme under the lock-up agreement regardless of whether the anchor shareholder was included in the class, the parties agreed to hold two scheme meetings and Snowden J did not rule on the class issue.

Key contacts

Russian Standard Finance

In 2013 A&O acted for The Co-operative Bank PLC on its liability management exercise to effect a recapitalisation of the bank to alleviate regulatory capital pressures faced by the bank. This included a scheme of arrangement of certain subordinated securities of the bank and amounted to the first consensual "bail-in" of a UK financial institution without which the bank potentially faced being subject to “resolution” measures under the Banking Act 2009. Autumn 2015 saw A&O acting on a transaction with similar aims - a recapitalisation of Russian Standard Bank, a large Russian retail bank, to avert a breach of regulatory capital ratios. Russian Standard Bank's capital had, as a result of large losses caused by, amongst other things, Russian sanctions and a deterioration in the domestic Russian economic performance, been eroded such that a breach of its regulatory capital ratios would have occurred unless the bank could be recapitalised. The transaction demonstrates that the flexible nature of schemes make them a useful option for resolving regulatory capital issues affecting not just UK based financial institutions but foreign financial institutions as well, thereby, for the benefit of all stakeholders, providing an alternative to formal "Resolution" measures being taken by relevant regulatory authorities.

Scheme jurisdiction not a concern

A&O acted for the debtor, Russian Standard Finance, a Luxembourg incorporated SPV that issued subordinated securities for Russian Standard Bank, the proceeds of which had been used to fund subordinated loans to Russian Standard Bank that formed part of its regulatory capital. Faced with a limited timetable, and concerns that a consent solicitation would not be deliverable across the two series of notes, Russian Standard Finance proposed an English scheme in respect of two of its series of notes (treated as a single class of creditors) pursuant to which noteholders would exchange their notes for a mix of cash and new notes issued by an affiliate of the bank's shareholder (effectively amounting to a quasi-equitisation of the notes). The bank considered that, absent the scheme going through, the notes would (pursuant to their terms) be written down in full and noteholders would receive nothing. Notwithstanding the issuer was incorporated in Luxembourg, because the notes were governed by English law and a number of noteholders were located in England, the English courts once again accepted jurisdiction in respect of the proposal.

No prior noteholder consultation

One unusual feature of the restructuring was that there was no noteholder consultation prior to the launch of the scheme. Shortly after launch, a group of noteholders constituting a blocking minority (in excess of 25%) indicated that, without improved terms, they would vote against the scheme. After a brief negotiation, and taking into account very limited flexibility in the timetable, the bank agreed to improve the offer to noteholders by amending certain terms including increasing the cash payment offer under the scheme. Notwithstanding the court had already convened the scheme meeting to vote on the original transaction, these amendments were made to the scheme without a further court hearing and the proposal was approved by the noteholders at the scheme meeting.

Key contacts

Celsa “Huta Ostrowiec” SP. z.o.o.

Following involvement on a number of other high profile steel industry transactions in 2015, summer 2015 saw A&O acting for a group of Polish and other international lenders with the aim of finally restructuring the PLN 2.3bn syndicated facilities of Celsa Huta, a Polish borrower within a large European steel manufacturing and products group, following years of negotiations and consideration. After years of trading difficulties and financial strains both in the steel industry as a whole and in the geographical areas in which Celsa Huta operates, its debt was restructured in 2011 and the maturity extended to 2017. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Redevelopment at that time provided a €35 million working capital facility in a gentle attempt to salvage the business, but that facility was not sufficient to withstand a subsequent uncovering of widespread VAT fraud within Poland which put pressure on steel prices in the area between 2011 and 2013. By 2014, Celsa Huta’s lenders had waived various interest payments and started negotiations in an attempt to recover their investment.

By summer 2015, a majority of lenders had agreed that Celsa Huta’s existing facilities should be re-tranched into two operating company senior secured loans due in December 2020 with new, half-amortising and half-bullet repayment schedules, more achievable maturity dates, a reduction in margin on amortising facilities and PIK interest on bullet facilities. A pre-agreed exit mechanism was also favoured, by which beneficial interests in Celsa Huta would be transferred to lenders under a conditional sale agreement upon the occurrence of certain trigger events (including non-payment of debt).

First scheme of a Polish corporate

Though a majority of the lenders had hoped for a consensual deal, three Polish banks representing around 10% of the debt by value did not support the deal. However, as the proposal had gained around 90% approval and faced with on-going financial strains, Celsa Huta proposed that the transaction should be implemented by way of an English scheme of arrangement.

The scheme that followed in August and September 2015 was the first English scheme to be undertaken in respect of a Polish corporate. Three classes of creditors were determined, based on (i) creditors who benefitted from separate existing security and (ii) creditors who held super senior tranches of existing debt. Unusually, a shortened timetable meant that no lock- up agreement was able to be entered into, requiring Celsa Huta and the supporting lenders to take a more active role in persuasion of and negotiation with less active and non-supporting lenders than would otherwise have been expected. This was effective, as a 100% turnout in voting was reached, with 83% by number and 90% by value voting in favour of the scheme.

Innovative solution to potential block on successful restructuring

Notably, in order to implement the pre-agreed exit mechanism with a diverse group of lenders (not all of who supported the proposal) by way of a conditional sale agreement, a trustee would be required to hold the Polish shares for the lenders upon the relevant trigger events and sell them in order to distribute proceeds to lenders at a later date; that trustee would require indemnification. However, it is a long-standing principle of law that an English scheme of arrangement may not be used to impose new obligations on any party without their agreement. To resolve this issue, A&O advised on an innovative “opt-in” procedure by which lenders would, following the Scheme Effective Date, be invited (but not obliged) to subscribe to a trust deed and shareholders’ agreement (TDSA) containing the relevant trustee indemnity. Any lender that chose not to opt-in would not benefit from certain rights under the restructuring documents, including the right to vote on matters under the TDSA, which included determining the process by which the shares will be sold after completion of the conditional sale. The English court was persuaded to implement the proposal as it was convinced that (i) the principle of fairness is not infringed by this arrangement, as a decision on opting in or out did not affect the value of any lender’s scheme claim or its treatment under the scheme and (ii) the undertakings to the court by certain supporting lenders that they would opt into the TDSA confirmed that there would be no prospect of failure to implement the process post-sanction.

Key contacts

1 Council Regulation (EC) No 1346/2000 of 29 May 2000 on Insolvency Proceedings

2 Regulation (EU) No. 1215/2012

3 While, strictly, having just one creditor domiciled in England should be sufficient, the courts have suggested that they will require a number of creditors that is not immaterial – what that number is has not been fully tested but it has been suggested that 10-20% by value is an appropriate minimum.